Written by: Muneyuki Okabe

Translated and edited by: Alex Strauss

Colors of the earth.

“At sunset, when I look between the mountains and the sky and see the colors of the skyline, I am inspired by its beauty. The emotions and sensations that spring up within—I think about expressing that in my work. ”

Midori Uchida speaks quietly, looking out at the sky from the garden of her atelier. Uchida-san is one of Japan’s leading contemporary pottery artists. Despite her stature as an artist, she doesn’t appear in public at all. She prefers to remain absorbed in her craft at her workshop high in the mountains of Gifu, beneath the panoramic sky.

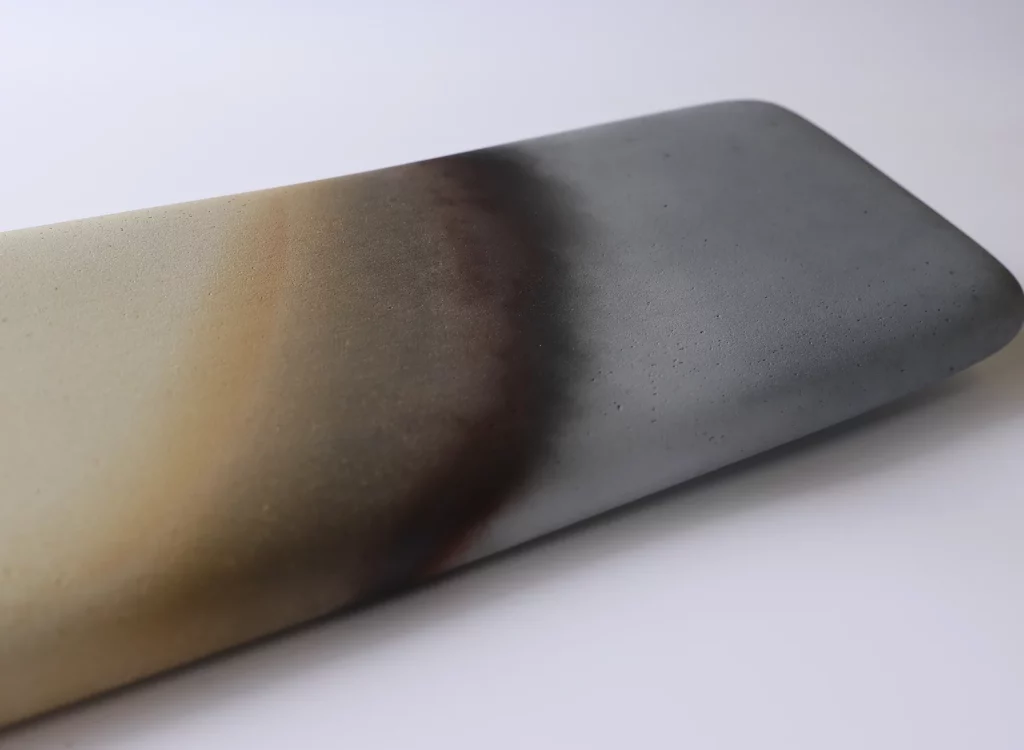

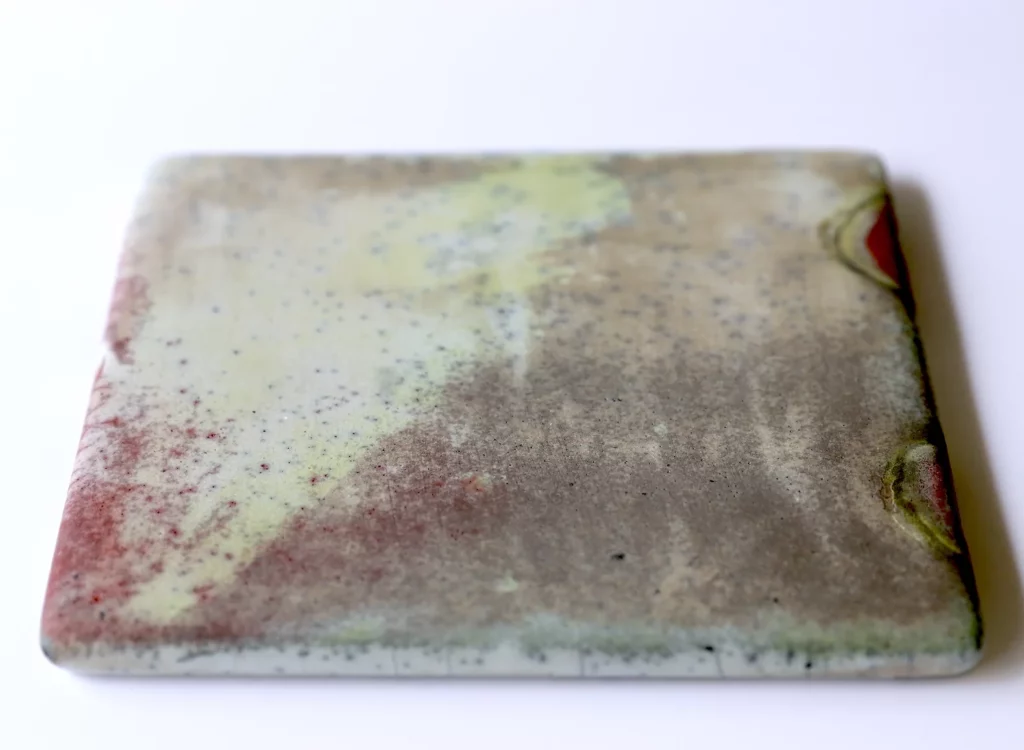

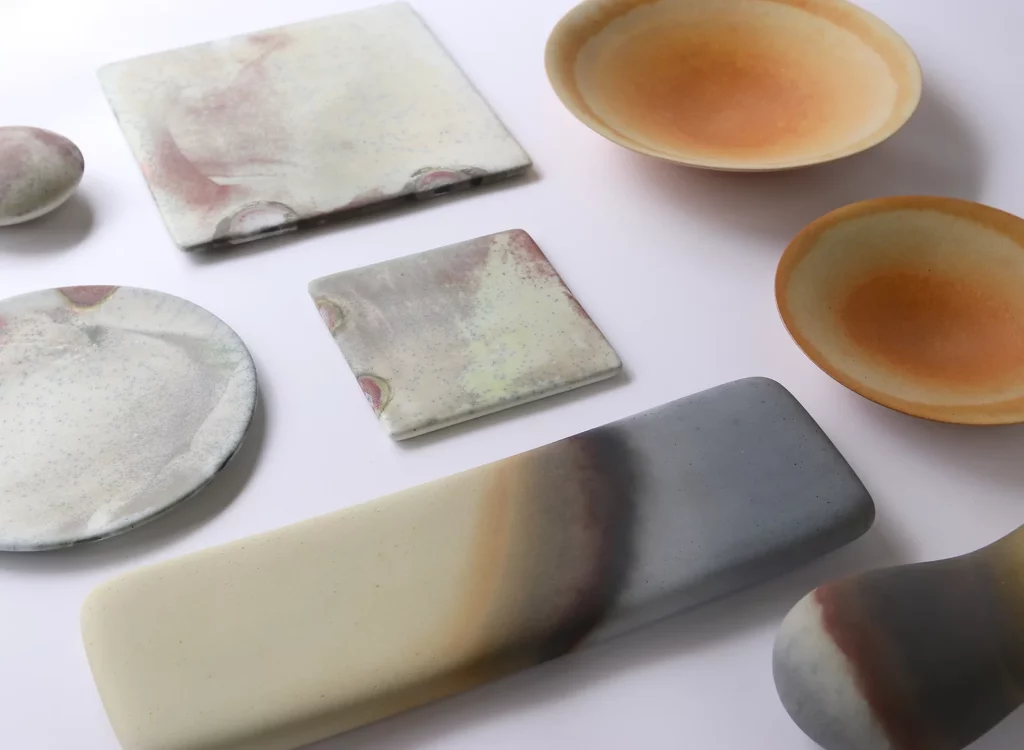

Unlike Uchida-san’s soft-spoken demeanor, her art is known for leaving lasting impressions. Her aesthetic, known as “landscape,” has a pale color gradation befitting the visual spectrum of a distant planet than anything earthbound. There is an element of mystique to it, like a dream, of something not belonging to this world though it is entirely of this world.

Soil and fire in a sacred land

What does it take to produce such captivating color? Uchida-san’s method is deceptively simple, involving only earthenware, fire, and the strategic use of rice husks. Using a ceramic art technique called carbonization firing, she can express colors without glaze or slip. For example, when baking a bowl, putting the bowl and rice husks together in a special container called a saya-bachi (sheath pot) facilitates incomplete combustion; through that process, color is born. However, Uchida-san cannot exercise total control over the color-creating process of carbonization firing, which she views as an indispensable benefit. For as with nature itself, no sunrise or sunset looks the same. Everything is irrepressibly dynamic, and that very fact enriches everything, including Uchida-san’s ceramics. The resulting hypnotic visuals are why she has been called a “genius of color.” And as irony would have it, the name “Midori 翠” is a Japanese word that refers to the pale color between blue and yellow found in nature, such as grass and leaves.

Midori’s formal training began in university, where she studied ceramics for four years. Then, she went on to study for another two years at the Ceramics Design Institute in Tajimi, Gifu, where she has remained ever since, making pottery for the last 13 years. It is a fitting locale, given Gifu Prefecture is Japan’s sacred land of ceramics—a reputation it has sustained for over five centuries.

Gifu’s culture of handcrafted wares dates back to Japan’s Sengoku (Warring States) period when warlord Oda Nobunaga’s passion for tea filtered its way into his domain’s economy. In Gifu, he ordered craftspeople to begin making tea bowls locally, ending dependence on Chinese craftsmanship and creating the basis for artisans to reimagine such crafts through a Japanese lens.

“As a student, I realized that I valued shape—that shape was fundamental for me; I was always searching for ones I connected with. It was my obsession.” Indeed, at first impression, Uchida-san’s work tends to catch the eye for its colors, but it also does so through the beauty of its shape, form, and curves. To create her wares, she uses a ceramic hand-building technique called tebineri. It is a primitive style that foregoes throwing clay with a potter’s wheel, relying primarily on one’s fingers for shaping. According to Uchida-san, tebineri offers a more direct translation from one’s imagination to handmade creation.

The joy catalyst

Young Midori Uchida aspired to ceramic mastery early on—perhaps too early. She tells a story of her youth when she nearly burned out before attaining the requisite knowledge, skills, and experience to develop beyond amateurism. Her goal was to become a master ceramicist by pushing herself to create more elaborate, ornate works of art, but she serendipitously found out that the opposite approach allowed her to refocus her priorities on the bare fundamentals of her craft.

“Raku-yaki (raku ware) allowed me to enjoy ceramic art more purely. It is, to put it simply, fun. It’s a joy to do.”

Uchida-san discovered her style by coincidence during raku ware crafting sessions with friends. She likens it to the similar magical dynamics of creating pottery, as soil, fire, and oxygen coincide to produce various colors.

In that sense, those joyful sessions crafting raku ware is where Uchida-san got her “start.” The style—now in its sixth century of existence—has a low barrier to entry. It involves molding clay by hand and baking it at low temperatures for a short time and is a technique in which amateur ceramicists can partake and flourish. In Uchida-san’s case, how raku ware baking causes light color changes drew her in further, leading her down a path to her current technique.

Nature’s beauty is universal

“As a child, my parents took me to various places outside Japan. We’d visit a foreign country and go mountain climbing. I was very fortunate to be able to see so many landscapes and scenic views.”

Uchida-san’s work is simultaneously a personal artistic expression meticulously crafted, while also an attempt to prompt the viewer into a kind of recall—to remember scenes of natural beauty in their life that resonated emotionally. She believes in the universal experience of awe-inspiring beauty, that everyone has had (and can have) such experiences, and believes nature itself is the most abundant supplier.

“I’ve also been thinking a lot lately about the role of positive feelings in my work. For some, anger, sadness, and suffering are sources of creation. I value positive feelings such as joy as a creative force. They are imbued in my work.”

Uchida-san is quiet and reserved. But in her work lies an intense, optimistic message to the world.

In this series of eight profiles, we will highlight the wonderful tableware and handcrafts of artisans in the Chubu region of Japan. It is an area steeped in the history and cultural legacy of some of the world’s finest handcrafted wares and the artisans who create them. Next spring, we plan to hold an exhibition of the artists featured in this series in the United States.

Featured writer

Muneyuki Okabe | Zen Resorts

Founder / CEO of Zen Resorts, a company that specializes in luxury travel in the countryside of Japan. He is a curator who cherishes Japanese traditional crafts and a journalist who has introduced them on TV programs.